Victims of cluster munitions are determined to bring about change.

As Switzerland presides over the Second Review Conference of the Convention on Cluster Munitions, the time is right to give voice to victims.

Lith Soyda is one of the victims of cluster munitions in Laos. In the centre of the image, he tells his story © Lasting Footprints.

He was only eight years old when he came upon a cluster munition. Today, Wahidullah Safi is 32 and lives in Laghman Province, which is east of Kabul. In this lush and mountainous region of Afghanistan, he is especially careful when he walks. He is well aware of the potential danger that unidentified objects on the ground can represent. When he was a young child, one such object changed his life forever. The moment he touched it, the munition exploded. Wahidullah realised instantly that he was about to lose his leg. And even though he lost consciousness only seconds later, he still has vivid memories of that fateful moment.

When he realises that he is telling his story for the first time, over the phone, to someone far away, he is overcome by emotion. Yet in Afghanistan, he often speaks to the media, mainly to raise public awareness, while also being active on social media. "Telling our stories," he explains, "sets a precedent, making the reality of cluster munitions more concrete, which helps everyone understand it better."

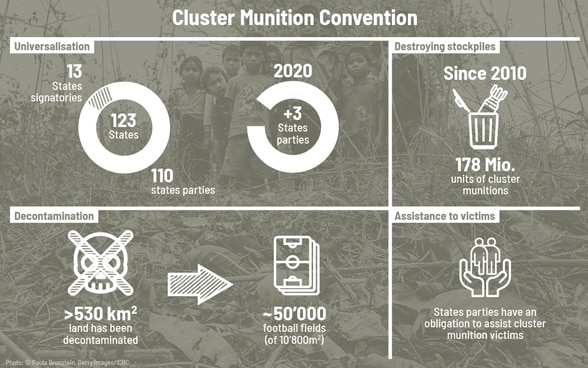

"The voices of victims who have been hit by cluster munitions and survived are fostering greater global awareness of the issue. Their words are helping to increase the stigma associated with these weapons," explains Hector Guerra. It was thanks to their voices that the International Campaign to Ban Landmines (ICBL), currently headed by Mr Guerra, was launched in 1992. With calls for disarmament growing worldwide in the early 1990s, this global campaign was created to give voice to victims and their families, and to translate into emotions the daily reality of people living in the midst of weapons that strike indiscriminately. The momentum generated by the ICBL gave rise, less than 20 years later, to the Convention on Cluster Munitions.

Laos, the most affected country

In Laos, the country most contaminated by these weapons, a young man tells of his disrupted childhood. Lith Soyda is one of the many children whose lives were turned upside down in a split second. He was only six years old when, on his way home from a swim with his friends in the river that ran past this village of Ban Soblap in the North of Laos, he unknowingly came into contact with a cluster munition.

In the dead of winter, chilled by the cold air, he tried to get a camp fire going in front of his grandparents' home. As the first embers began to glow, a powerful explosion struck, sending him into a coma that lasted more than a day. He awoke in a hospital bed – the fingers on his right hand had been amputated and he had lost the use of his right eye. "My parents spent all their money to save me, after which I needed months of rehabilitation to recover some semblance of a normal life," he explains.

What does the future hold for victims?

Wahidullah Safi in Afghanistan and Lith Soyda in Laos have something else in common: an iron will in their fight for the rights of victims and survivors. By speaking out, each supports people with disabilities in their own country and worldwide in enduring the sometimes difficult conditions they face.

Lith Soyda, today aged 18, is still a high school student. Supported by Handicap International, he is also taking an introductory course on volunteering while fighting persistently for people with disabilities in Laos. "In Laos, people with physical disabilities are at a disadvantage in the labour market compared to others. I am hoping to be able to build a successful career despite my disabilities. In fact, I am committed to making that happen."

As for Wahidullah, he has been able to keep studying and find employment despite his disability. Among other things, his job includes helping people or groups with disabilities to reintegrate into society, supporting the family members of civilian victims of armed conflict, and defending people in precarious situations. "I plan to stay engaged in protecting the most vulnerable, those who are also the ones most exposed to cluster munitions," he explains. These strong-willed young victims are not about to let fate get the better of them.