Winston Churchill: art, friendship and foreign policy

Confident, cosmopolitan and creative: in his address at the Churchill Symposium, Federal Councillor Ignazio Cassis takes a look at Switzerland's role in Europe and Winston Churchill's special relationship with this country. Thereby, raising the question: What does an entrepreneur from Urdorf have to do with the colourful history of Switzerland's foreign policy?

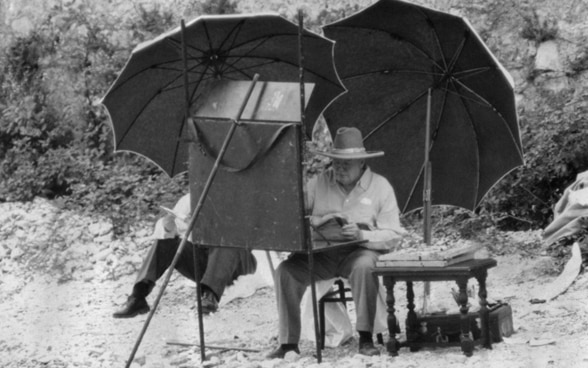

The 1946 visit remained Winston Churchill's only trip to Switzerland. Nevertheless, the famous politician remained closely connected to the country for the rest of his life - not least thanks to his Swiss friend Willy Sax. Photograph: Zurich, 1946 © Keystone

Nearly 75 years have passed since Winston Churchill, one of the most brilliant personalities in modern world history, stood here in Zurich, in a very different world to the one we know today. 1946 was a year marked by the still-recent memories of two world wars, a year when Europe lay in ruins. "What will become of this continent?" "What is Europe?" "Who are we?"

These are questions in search of a sense of common identity. Questions that are as important now as they were in 1946. Ladies and gentlemen, it is my great honour to open the Churchill Europe Symposium today. Our lives in 2021 may seem far removed from the realities of 1946, but there are many similarities too. Europe is once again emerging from a state of shock – brought to a standstill not by war, but by a global virus. The economy is only now beginning to recover, and people are torn between the desire for greater personal freedom, national sovereignty, and the issue of European solidarity.

Switzerland and the UK: between national sovereignty and European community

Winston Churchill's interest in the future of Europe, his call to found a kind of United States of Europe, and the effort to combine a sense of common identity with national pride are topics that are as relevant today as they were in 1946. This applies as much to the UK's departure from the EU as it does to the discussions on bilateral relations between Switzerland and the European Union.

Although the Brexit deal cannot be compared to the Swiss framework agreement, it is nonetheless interesting that the trilateral relationship between Switzerland, the EU and the UK continues to play a key role in mapping out the future of Europe. Indeed, it was no coincidence that Churchill made his famous Europe speech here in Zurich, though the reason had less to do with world politics than you might think.

Painting as a therapy for political defeat

On 19 September 1946 Churchill travelled to Zurich, where he made his famous Europe speech. But the reason behind his visit wasn't an official invitation from the Federal Council, as one might suspect of a statesman of his standing. No, Churchill was in fact here on a private initiative. The war time prime minister's trip was motivated by personal relationships, and by his unbridled passion for painting. Yes, you heard me correctly: his passion for painting. Churchill was an enthusiastic and, above all, extremely talented painter who spent almost all of his free time in front of the canvas. And it was Switzerland that he had to thank for this passion. For Churchill would probably not have become a painter, or spoken in Zurich in 1946, had it not been for his friends in the Swiss art world. But let’s start at the beginning.

Churchill was a late bloomer when it came to painting. He only began experimenting with brushes and paint at the age of 40, at a time he described as his 'darkest hour'. After the failed Allied offensive on the Gallipoli peninsula in the First World War, Churchill was forced to resign as First Lord of the Admiralty. The passionate politician and military daredevil was plunged into an existential crisis. Being a mere spectator in this global tragedy was more than Churchill could bear. In his anger and despair, he reached for a paintbrush.

Politics and art: a joke blossoms into a lifelong friendship

Churchill met his first and most important art teacher in Paris in 1915 – a Swiss man by the name of Charles Montag. The artist had emigrated to France from Winterthur and made a name for himself as a painter – though he is most famous as a fierce advocate of the French Impressionists. His first meeting with Churchill very nearly ended in a war of words. Churchill asked Montag what he thought of his paintings, to which the artist responded, in French: "Si vous faites votre politique comme votre peinture, l'Europe est fichue" – "If your politics are anything like your painting, Europe is lost."

His words made quite an impression. The otherwise eloquent British firebrand wasn't sure whether to show this quick-witted Swiss man the door or simply laugh. Fortunately, Churchill decided on the latter. After all, as Churchill maintained, he had come to Paris specifically to meet two people: the French president, Raymond Poincaré, and the man he was speaking to – Charles Montag.

V for Victory and a poker face in an open-topped cabriolet

It was the beginning of a wonderful friendship, and a shared passion for painting. Three decades and another world war later, that passion would take Churchill on a journey to Switzerland. For Churchill, by then a famous statesman, was not drawn to Zurich by high-level politics, nor by the local table wine – which quite literally left a bad taste in his mouth. No, what brought him to Switzerland in 1946 were the vibrant colours of the paint maker Willy Sax, who ran the modest family business Sax-Farben Ltd. in Urdorf, near Zurich. The small company's reputation had travelled as far as England, and its paints had found their way into Churchill's parlour. Churchill wanted to finally meet the man who supplied the cherished materials for his aesthetic pursuits.

Before the evening of his famous speech on Europe here in this Aula, Churchill asked Willy Sax to visit him at the Dolder Grand hotel. He immediately liked the Swiss paint maker, and they agreed to meet in Zurich's old town the next day so that Sax could show Churchill the proper way to use his painting materials. Churchill even postponed his return flight to London for this second meeting with his new Swiss friend, but asked that it be kept secret in order not to attract crowds. The meeting took place as planned, but any hopes of secrecy proved somewhat optimistic. When Churchill left the paint shop, he found that a huge crowd of people had gathered in front of it. Ever the showman, Churchill kept his poker face as he got into his open-topped cabriolet, made the sign for victory and was driven hastily away.

Painting holidays together, a shade of blue for Churchill, stockings for his wife

Churchill never returned to Switzerland, but his attachment to the country, and to Willy Sax in particular, was an enduring one. The two friends saw each other regularly. Sax visited his fellow painting enthusiast many times at Chartwell House, and was also a welcome guest at 10 Downing Street when Churchill was prime minister again between 1951 and 1955.

Over the years, the two men wrote each other more than a hundred letters and telegrams, often exchanging gift packages between Urdorf and London. Sax would send cured ham, schnapps, packets of Knorr soup, Swiss chocolate and highly fashionable nylon stockings for Churchill's wife. At the heart of their friendship, though, were the painting holidays they shared on the Côte d'Azur. Churchill the artist was captivated by the Mediterranean light, and Sax the paint maker brought the perfect colours to capture it in all its splendour. At the prime minister's request, Sax even created a special tone of paint for his British friend: a sky blue – or 'Churchill blue'.

An artists' friendship paves the way for political diplomacy

This painters' diplomacy, if I can call it that, covered much more than just a shared enthusiasm for art. No other Swiss person had a closer relationship to Winston Churchill than Willy Sax. The Swiss businessman's personal connection to Churchill increasingly saw him adopt the role of a political mediator. Sax became a kind of relay station between Churchill and Switzerland, a private ambassador of sorts for friendly exchanges between the two countries.

In the spring of 1956, for example, Sax travelled to London with the mayor of Zurich, Emil Landolt. The City of Zurich wanted to organise an exhibition of Churchill's paintings, and Sax was to bring Landolt face to face with the artist himself. However, Churchill cancelled the meeting at short notice. He didn't know this Landolt fellow, after all, and couldn't just receive every mayor who turned up from around the world. Sax, on the other hand, was most welcome. Churchill and his Swiss friend enjoyed a steak and kidney pie, drank whisky, and smoked cigars – while the mayor from Zurich took a stroll outside.

Swiss collegial government for the people, not for state visits

But it wasn't always on the British side of things that Sax's diplomatic efforts failed. Occasionally it was Swiss tradition that stood in the way. In 1955, for example, Sax made a further attempt at private diplomacy – this time at the highest level. Sax travelled to Bern to meet the Swiss president and foreign minister, Max Petitpierre, whom Churchill had described as a first-class man on his visit to Switzerland nine years earlier. Sax's plan was for Petitpierre to finally be reunited with the prime minister and accompany the two friends on their painting holiday. Churchill sent the Swiss president his best regards – via Sax, of course – and told him he looked forward to seeing him soon.

But the meeting never came to pass. The reason: Switzerland's policy of collective government. Petitpierre gave Sax the following message: "It would be a pleasure to see Sir Winston Churchill again, and I would gladly have visited him in Monte Carlo. Unfortunately, it will not be possible for me to do so this year, as custom dictates that the Swiss president cannot leave Switzerland during his year in office." Through this cautious travel policy, President Petitpierre was demonstrating that Switzerland did not have a true head of state. He saw himself only as first among equals in the seven-strong Federal Council – his role was to be there for his fellow citizens, literally and figuratively. They were more important, after all, than the statesman and artist Winston Churchill.

Small, but eminently capable: how Switzerland resembles Willy Sax

I discovered this and many other wonderful stories about the British prime minister's little-known Swiss connections in the book Champagne with Churchill by the Swiss historian Philipp Gut. The episodes it describes struck me not only as historically interesting, but also quite amusing. I see in them a reflection of Swiss foreign policy. Isn't Willy Sax's mediation as a private citizen a little reminiscent of Switzerland's mediation in the international context? As a small, independent and neutral state that favours right over might, we are predestined to act as an intermediary in conflicts, quite in keeping with our tradition of good offices.

Now, this isn't an application to take over the job of Michel Barnier – who I'll give the floor to in just a moment. Nor am I suggesting that the EU and the UK are in a state of war. Heaven forbid. Instead, this is a plea for Swiss foreign policy to be both selfless and self-assured, just like the amazing small businessman Willy Sax. He had no anxiety or inferiority complex about contacting a statesman as important to world history as Winston Churchill. He remained modest and down-to-earth, always presenting himself as a messenger and mediator for the concerns of others. And what's good enough for Willy Sax is good enough for Switzerland too.

Loving freedom and defending the rights of others

Winston Churchill saw it the same way, incidentally. In 1946, shortly after visiting his friend Willy Sax in Zurich and delivering his famous speech on Europe, Churchill emphasised to the Federal Council Switzerland's distinctive combination of independence and openness to the world. Switzerland, he told them, proved that one could love freedom and still respect and promote the rights of others.

Standing here today as head of the Federal Department of Foreign Affairs, I could hardly put it better than Churchill did back then. This globally conscious sovereignty, if I may call it that, is the precondition for Switzerland's international and humanitarian commitments. Confident, cosmopolitan and creative: let's have the courage to use every colour in the palette of world politics. Let's all be a little more like Willy Sax.